Has AI used in nature been a positive force?

MIT Review: Intelligent Mining, Conservation with Support of AI Tools

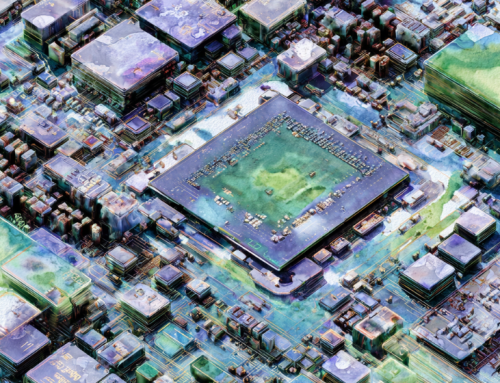

Quietly, one of the world’s largest mining companies is developing the world’s first “intelligent mine” in Australia. At first glance, the idea of melding AI and computers with a 31 mile long, 3-mile wide coal mine might seem a little odd. But since AI has invaded nearly every business arena in the last 20 years. Now it is being programmed for invading nature.

And the idea of AI mixing with nature caused author Peter Dauvergne to write a book entitled, AI in the Wild: Sustainability in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. This prompted writer Angela Chen to review Dauvergne’s book in undark.org this week.

The mining company mentioned above is Rio Tinto, truly one of the world’s largest manipulators of the planet. With the help of a $2.6 billion investment and by applying artificial intelligence and data analytics, Rio Tinto hopes to automate parts of the mining supply chain, improve safety, cut downtime, and optimize extraction. Australia’s Koodaideri is slated to become Rio Tinto’s first “intelligent mine” and one of the most technologically advanced mines in the world by early 2022.

For political scientist Peter Dauvergne, the Koodaideri mine represents the tensions that arise when AI meets the environment. Artificial intelligence is often presented as a solution for protecting animals and saving the planet, but when deployed by companies like Rio Tinto, the same methods can also be used to deplete natural resources more quickly. AI is simply a tool that increases efficiency, Dauvergne argues, and it is a tool controlled by corporations whose priority is efficiently making money. (In August, the CEO of Rio Tinto faced calls to resign after the company demolished an Aboriginal site in order to access the ore.) In the end, it will be human values, human systems of accountability, and human political will that make a difference.

But first, Chen writes, the good news. Throughout the book, Dauvergne highlights several intriguing examples of AI-enhanced conservation tools. The nonprofit Rainforest Connection, for example, has built a system of solar-powered sensors high up in the trees of endangered forests. Repurposed from old cell phones, these sensors use Google’s open-source machine-learning platform to monitor and detect sounds — birds and jaguars and monkeys, but also the buzz of illegal chainsaws — from nearly a mile away. This information can be relayed in real-time to rangers trying to protect the trees from would-be loggers.

Other feel-good examples include drones with night vision that help catch poachers, underwater robots that guard the Great Barrier Reef against harmful species, and a facial recognition program for chimps that can cut down on wildlife trafficking. Earth-imaging startups use AI to more accurately analyze satellite data, which in turn provides a broader view of global environmental change.

But it is not all good news. Dauvergne has waved some red flags with his book. In Dauvergne’s view, these AI solutions ignore the forest for the trees.

“AI technology can take us only so far toward lasting, far-reaching solutions, as it has little power to confront the underlying political and socioeconomic forces exploiting natural resources and destroying nature for profit,” he writes.

Monitoring poachers or making Amazon warehouses less energy-intensive does not change the factors that lead to poaching and the demand for two-day shipping in the first place. And often, the companies that brag about corporate social responsibility do so to help customers feel good about their desire to buy new and buy more; they promote consumerism under the guise of environmentalism.

Another concern is all the high tech going into farming. Does it increase our crop yield or does it deplete the earth at an even faster rate? Should the fact we only recycle 1/5th of the e-waste we produce enter into the equation since much of it ends up illegally dumped in developing countries? Will we be leaving computer junk behind when these well-intentioned projects are finished? If you would like more information on this subject click the link below. Chen’s article and Dauvergne’s book should give us all pause before all these new ideas take us beyond a reasonable use of AI in the great outdoors.

read more at undark.org

Leave A Comment