Scientists used RNN that can create toxicity capable of being used as a biological weapon.

Researchers Discover How AI Can Turn Drug Formulas into Dangerous Weapons

While working on an algorithm that creates new drug formulas, two researchers were hit with an unanticipated ethical problem. The power of AI can be flipped from doing great things to creating horrible weapons. Rebecca Sohn writes this week on scientificamerican.com, a detailed story about ethics in AI, or the lack of it.

In 2020 Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, a company that specializes in looking for new drug candidates for rare and communicable diseases, received an unusual request. The private Raleigh, N.C., firm was asked to make a presentation at an international conference on chemical and biological weapons. The talk dealt with how artificial intelligence software, typically used to develop drugs for treating, say, Pitt-Hopkins syndrome or Chagas disease, might be sidetracked for more nefarious purposes.

So trying to anticipate such a biological weapon two scientists took the challenge to heart.

In responding to the invitation, Sean Ekins, Collaborations’ chief executive, began to brainstorm with Fabio Urbina, a senior scientist at the company. It did not take long for them to come up with an idea: What if, instead of using animal toxicology data to avoid dangerous side effects for a drug, Collaborations put its AI-based MegaSyn software to work generating a compendium of toxic molecules that were similar to VX, a notorious nerve agent?

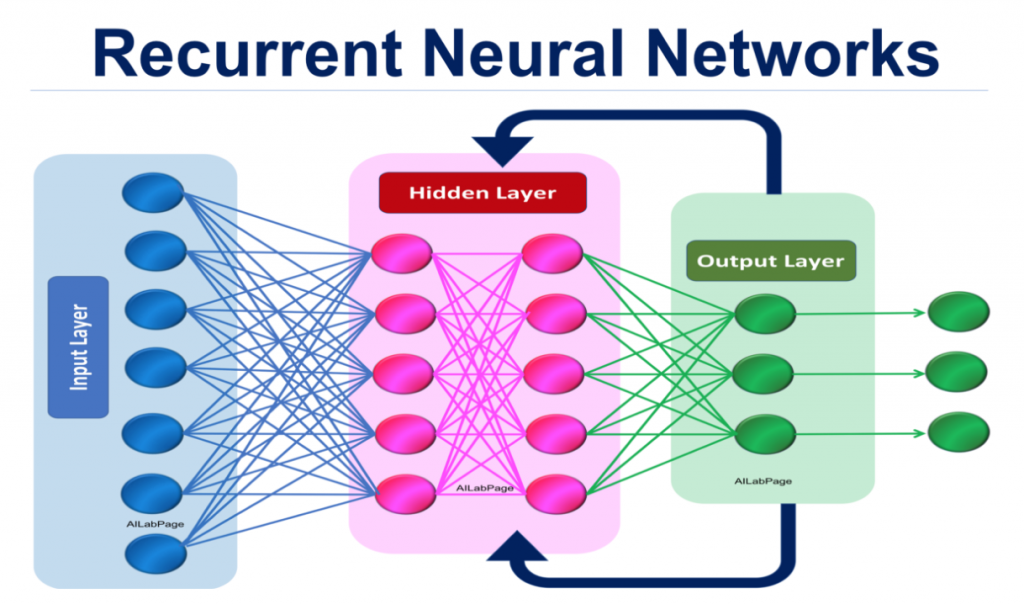

They found a problem with the Mega-Syn program. The RNN implementation called MegaSyn utilizes a state-of-the-art multi-objective optimization algorithm to optimize multiple parameters simultaneously during the RNN training. This allows for the creation of synthetic molecules that might prove useful in various medical fields. Or it might raise serious ethical questions.

When AI Crosses Ethical Boundaries

The team ran MegaSyn overnight and came up with 40,000 substances, including not only VX but other known chemical weapons, as well as many completely new potentially toxic substances. All it took was a bit of programming, open-source data, a 2015 Mac computer, and less than six hours of machine time.

In six hours these researchers saw immediately how less scrupulous people might abuse this discovery.

“It just felt a little surreal,” Urbina says, remarking on how the software’s output was similar to the company’s commercial drug-development process. “It wasn’t any different from something we had done before—use these generative models to generate hopeful new drugs.”

In its study, the company’s scoring method revealed that many of the novel molecules MegaSyn generated were predicted to be more toxic than VX, a realization that made both Urbina and Ekins uncomfortable. They wondered if they had already crossed an ethical boundary by even running the program and decided not to do anything further to computationally narrow down the results, much less test the substances in any way.

Their results and concerns even made it to the White House level. Urbina, Ekins, and their colleagues even published a peer-reviewed commentary on the company’s research in the journal Nature Machine Intelligence—and went on to give a briefing on the findings to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

But other researchers said even though some AI can create frightening scenarios in a digital universe, they all can not be reproduced in our actual universe.

“The development of actual weapons in past weapons programs have shown, time and again, that what seems possible theoretically may not be possible in practice,” comments Sonia Ben Ouagrham-Gormley, an associate professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government’s biodefense program at George Mason University, who was not involved with the research.

But is that comforting enough for us to just put those possibilities aside about worrying about whether a new drug could be turned into a bio-weapon? Especially if it’s the same AI creating toxic molecules just by adjusting the program? Right now, it is a problem that’s still a little way down the digital road.

For their part, Urbina and Ekins view their work as a first step in drawing attention to the issue of misuse of this technology.

“We don’t want to portray these things as being bad because they actually do have a lot of value,” Ekins says. “But there is that dark side to it. There is that note of caution, and I think it is important to consider that.”

read more at scientificamerican.com

Leave A Comment