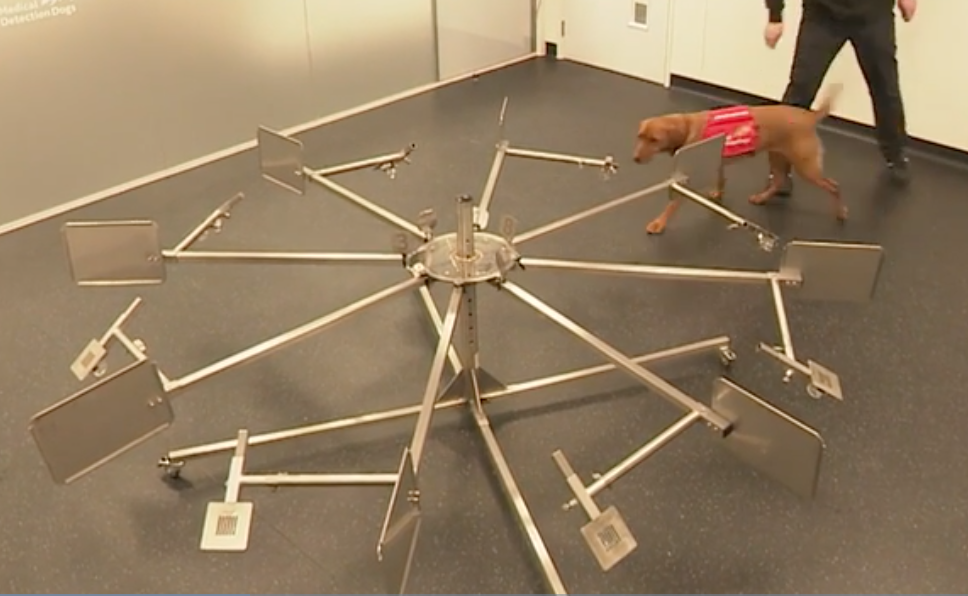

Medical detection dogs training in U.K. may soon have AI competition.

UK Researchers Create an AI with a Nose for Medical Problems

People have long known about the sensitivity of a dog’s nose. They sniff out treats, drugs, explosives and more. Dogs can also sniff out disease in a person’s body by sniffing their urine. An article on news.mit.edu explains how an AI algorithm being trained to be as useful as a dog’s nose when it comes to identifying human diseases.

Numerous studies have shown that trained dogs can detect many kinds of disease — including lung, breast, ovarian, bladder, and prostate cancers, and possibly Covid-19 — simply through smell. In some cases, prostate cancer for example, dogs had a 99 percent success rate in detecting the disease by sniffing urine samples.

But it takes time to train such dogs, and their availability and longevity is limited. Scientists have been hunting for ways of automating the amazing olfactory capabilities of the canine nose and brain, in a compact device.

Now, a team of researchers at MIT and other institutions has come up with a system that can detect the chemical and microbial content of an air sample with even greater sensitivity than a dog’s nose. They coupled this to a machine-learning process that can identify the distinctive characteristics of the disease-bearing samples.

Researchers say the result could be an automated odor-detection system that could be integrated into a cellphone.

Published in the journal PLOS One, the research paper was authored by Claire Guest of Medical Detection Dogs in the U.K., Research Scientist Andreas Mershin of MIT, and 18 others at Johns Hopkins University, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and several other universities and organizations.

“Dogs, for now 15 years or so, have been shown to be the earliest, most accurate disease detectors for anything that we’ve ever tried,” Mershin says. And their performance in controlled tests has in some cases exceeded that of the best current lab tests, he says. “So far, many different types of cancer have been detected earlier by dogs than any other technology.”

The Detection System

Mershin and the team developed, and continued to improve on, a mini detector system that incorporates mammalian olfactory receptors stabilized to act as sensors, with data streams tracked in real-time by a typical smartphone’s capabilities. He says the system could potentially pick up early signs of disease far sooner than typical screenings.

In the latest tests, the team tested 50 samples of urine from confirmed cases of prostate cancer and controls known to be free of the disease, using both dogs trained and handled by Medical Detection Dogs in the U.K. and the miniaturized detection system. They then applied a machine-learning program to find similarities and differences between the samples that could help the sensor-based system to identify the disease. In testing the same samples, the artificial system was able to match the success rates of the dogs, with both methods scoring more than 70 percent.

While the physical apparatus for detecting and analyzing the molecules in air has been under development for several years, with much of the focus on reducing its size, until now the analysis was lacking.

“We knew that the sensors are already better than what the dogs can do in terms of the limit of detection, but what we haven’t shown before is that we can train an artificial intelligence to mimic the dogs,” he says. “And now we’ve shown that we can do this. We’ve shown that what the dog does can be replicated to a certain extent.”

The article by David L. Chandler is extensive.

read more at news.mit.edu

Leave A Comment