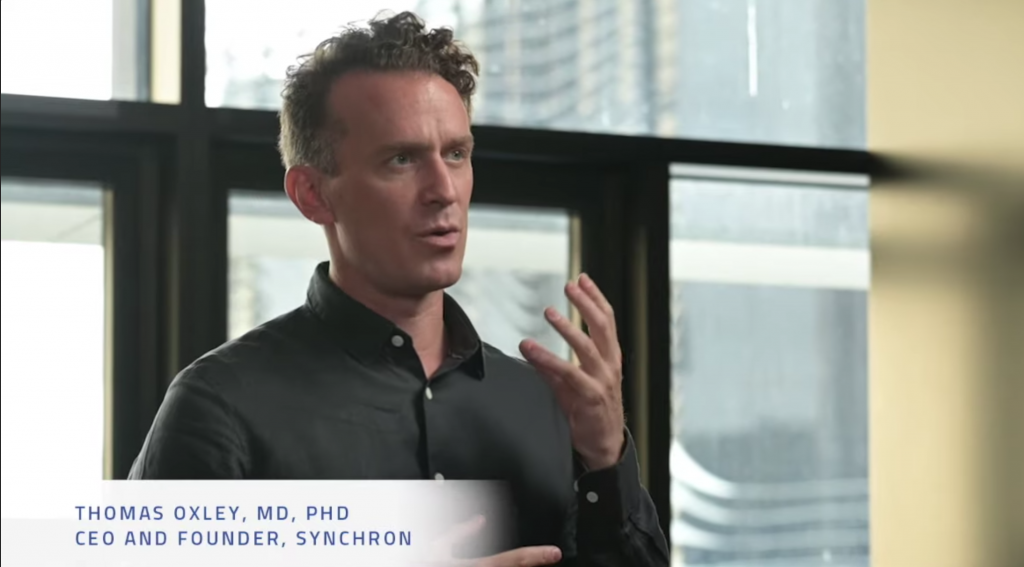

Synchron’s Founder/CEO explains the Brain-Computer Interface in this video. (Source: Synchron)

Synchron’s First Brain-Computer Implant Leads to Major Improvement for Paralysis Patient

It has arrived. The next level of the human-computer interface. It isn’t with who you might think it would be. That means it isn’t Elon.

It happened July 6th this summer. This interface involves a gentleman named Thomas Oxley. We got our story from wired.com this week and it will excite some of us and frighten others.

Thomas Oxley, the founder/CEO of Synchron, a company creating a brain-computer interface, or BCI, is heading a controversial new tech some have compared to an episode of the dark sci-fi TV series “Black Mirror.” BCI devices work by eavesdropping on the signals emanating from the brain and converting them into commands that then enact a movement, like moving a robotic arm or a cursor on a screen. The implant essentially acts as an intermediary between mind and computer.

“[Black Mirror is] so negative, and so dystopian. It’s gone to the absolute worst-case scenario … so much good stuff would have happened to have gotten to that point,” he says, referring to episodes of the show that demonstrate BCI technology being used in ethically dubious ways, such as to record and replay memories.

The “good stuff” is what Oxley is trying to do with his company. And on July 6, the first patient in the US was implanted with Synchron’s device at a hospital in New York. (The male patient, who has lost the ability to move and speak as a result of having amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—a progressive disease that affects nerve cells— has requested anonymity on the basis that he did not wish to promote the device before “experiencing its pros and cons.”)

The good news is they didn’t have to crack open the skull of the patient or interfere with his brain tissue. They inject the device through the jugular vein, into a brain blood vessel.

The device enables patients to control the mouse of their personal computer and use it to click. That simple movement could allow them to text their doctor, shop online, or send an email. The digital world has already seeped into every corner of modern human existence, providing all sorts of services—“but to use them, you need to use your fingers,” Oxley says. For the estimated 5.6 million people living with a form of paralysis in the United States, that access isn’t always available.

In August 2020, Synchron was granted an investigational device exemption from the FDA, allowing it to become the first company to conduct clinical trials of a permanently implanted BCI. To reach this point took five years and a “huge amount of work,” says Oxley. A trial in Australia followed four patients who had been implanted with the device for 12 months and suggested that such prolonged use of the device was safe.

Oxley dreams of a million implants a year, which is how many stents and cardiac pacemakers are implanted annually. That goal is about 15 to 20 years away, he figures. And he appreciates the discourse surrounding the technology, even if it does irk him.

“What I want the world to understand is that this technology is going to help people,” he says. “There seems to be a theme around the possible negative aspects of this technology or where it might go, but the reality is that people need this technology, and they need it now.”

Grace Browne has written an interesting piece that outlines the ethical, legal, and social risks of commercial use of the technology and its access to neural data. Questions include: “How long should that data be stored, what should it be used for outside of the device’s immediate application, who owns the data, and who gets to do what they want with it?”

read more at wired.com

Leave A Comment