UK Scientists Seek First AI Patent for Product Developments

British AI researchers are testing the legality of submitting two patents for inventions created by an AI machine called “Dabus” at the University of Surrey in the United Kingdom, according to a story in The Financial Times of London. The name Dabus is an acronym for “Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience.”

U.S., UK and European patent laws recognize only individual humans as inventors.

Dabus was created by Dr. Stephen Thaler, an AI expert based in Missouri, who drew on thousands of pieces of abstract pieces of information, including words and images, to produce complex concepts.

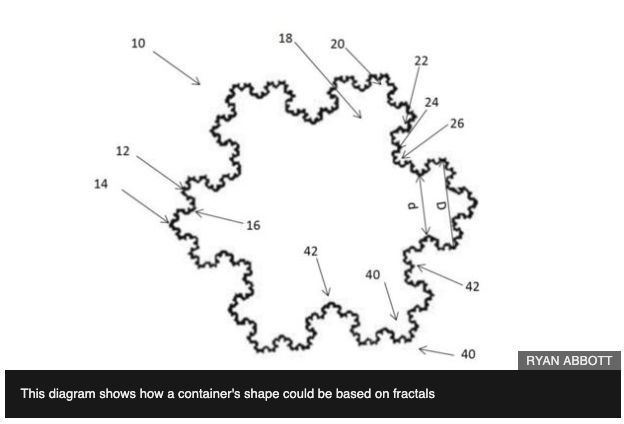

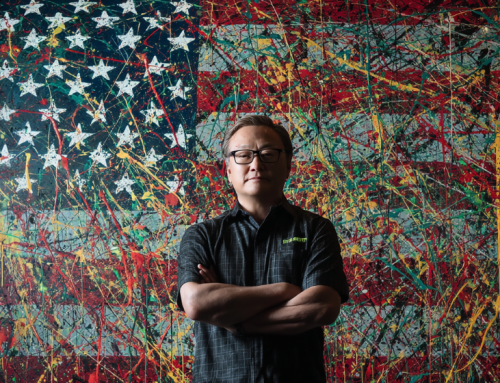

Programmed by an AI team at the UK university, Dabus invented a food container and an emergency flashing light—nothing space age, but rather practical objects of use to the masses. Ryan Abbott, professor of law and health sciences at the University of Surrey, submitted patent applications to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the European Patent Office and the UK Intellectual Property Office.

The design of the food container enables it to change shape to make it easier for robots to grasp. The flashlight system, also called a “neural flame” draws attention in emergency situations. A story in Futurism.com describes the inventions as the AI’s “fractal-based easier-to-grasp food container that it designed, as well as a lamp that it built to flicker in a pattern that mirrors brain activity.”

The patent describes the value of the emergency light as mimicking “the speed of thought” in the brain’s limbo-thalamocortical system: “The present invention relates to devices and methods for attracting enhanced attention. More specifically, the present invention relates to beacons for sustaining enhanced interest/attention, as well as to beacons with symbolic importance. In the prior art, signal indicators and beacons are typically based upon color, brightness, periodic flashing frequency, rotational pattern, and motion, but not fractal dimension.”

In a BBC story, Abbott argued for the validity of granting a patent to an algorithm.

“So with patents, a patent office might say, ‘If you don’t have someone who traditionally meets human-inventorship criteria, there is nothing you can get a patent on,’” University of Surrey law professor Ryan Abbott told BBC. “In which case, if AI is going to be how we’re inventing things in the future, the whole intellectual property system will fail to work.”

The Furturism writer Dan Robitzski, explains that the filing will be problematic because, “even the world’s best AI systems are merely tools — they’re not alive or sentient, and they’re not actually ‘creative’ as a person might be.”

A spokesperson from the European Patent Office told the BBC that granting a patent to an AI algorithm would create unforeseen legal precedents.

“The current state of technological development suggests that, for the foreseeable future, AI is… a tool used by a human inventor,” the unnamed spokeswoman told BBC. “Any change… [would] have implications reaching far beyond patent law, ie to authors’ rights under copyright laws, civil liability and data protection. The EPO is, of course, aware of discussions in interested circles and the wider public about whether AI could qualify as inventor.”

Abbott, the reasearch leader, said he expects it will take years for the patent offices to resolve the issue. A Techxplore.com article reviewed current case law to highlight the legal conflicts in the patent cases. Already some legal experts are calling for changes in current laws to recognize AI developments.

“We call on policy makers to rethink current patent law governing AI systems and replace it with tools more applicable to the new (3A) era of advanced automated and autonomous AI systems,” stated Shlomit Yanisky-Ravid (Yale Law) and Xiaoqiong (Jackie) Liu (Fordham) in Cardozo Law Review, arguing that traditional patent law had become “outdated, inapplicable and irrelevant.”

Leave A Comment