Partners Leverage Tech Advances for Info-Driven War

Since the beginning of the Global War on Terror and continuing at an ever-increasing clip, the U.S. military has shifted towards high-tech, information-driven gear and tactics via help from the private sector. The Pentagon has formed new swift-moving agencies to help hone the military’s technological edge.

Using innovations such as AI, drones, big data, and biometrics, the military is preparing for a century where superpowers and even traditionally low-tech stateless groups such as terrorist organizations are increasingly turning to high-tech means of fighting.

A Sailor in Iraq pilots a small ground robot used to investigate potential IEDs and search danger areas. Drones and robots have seen increasing combat use in the past ~15 years. Via U.S. Navy.

While the generation of soldiers who first deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan were Vietnam-era veterans or children of the eighties and nineties, using Cold War era equipment and tactics, the nearly two-decades-long Global War on Terror has seen a new tech-savvy generation deploy with ever-increasingly high-tech equipment in wars governed by chaos, uncertainty and the disruption incurred by the emergence of a global tech economy amidst the changing nature of conflict.

Soon, American teens may find themselves deployed to the same combat zones their mothers and fathers once patrolled in what even military strategists have taken to calling the “Long War” or “Forever War” without a hint of irony.

During the first decade of the Global War on Terror, the U.S. military began a shift from its Cold War-era mindsets and tactics towards the realities of the new form of warfare it faced, adapting to the foreign terrain of counterinsurgency. Ideologies and information became both the new weapons and primary landscapes in the battlefield, ultimately proving far more important than bombs or bullets.

Tribal affiliations, networks—social and digital alike—and the “human terrain” of a conflict presented crucial challenges and opportunities that the U.S. turned towards technology to solve; the smart bombs and overwhelming firepower of the late cold war could soundly win battles, but the overall war has been, arguably, contested or even “won” in some regions by farmers, clerics and drug lords with basic cell phones, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), 60-year-old rifles and—most importantly—the ability to control and hide their forces and weapons among the tribes and streets of their birth.

Countering the new nature of warfare and novel threats posed by cheap and/or technologically ingenious weapons, the military also adopted new technologies: within the span of the War on Terror, the military has employed advanced surveillance cameras to scan the countrysides and bazaars, radio sensors to intercept electronic communications, biometric scanners to find adversaries among a populace, remote-controlled robots to destroy explosives, electronic countermeasures to thwart IEDs, and drones to surveil or kill adversaries in locations too distant, dangerous, or politically distasteful for conventional strikes.

A Marine uses a SEEK, which incorporates an iris scanner, fingerprint pad, and facial recognition technology, to identify an Afghan man. Without uniforms, stateless 21st-century adversaries are able to move through communities in plain sight, using coercion or benefiting from local loyalties. Via U.S. Marine Corps.

As the U.S. military continues to evolve along these lines to create more capable counter-insurgents, even frontline grunts have started to use technologies that circa 9/11 were either inconceivable or relegated to Top Secret missions.

The U.S. Marine Corps, for example, recently announced what may become one of the most foundational overhauls in the organization’s recent history.

Retooling the Marine Corps’ frontline rifle squads—a group of about 13-15 Marines and Sailors divided into 3 fireteams—with new equipment and armament, the Marines’ move includes integrating a “Squad Systems Operator” in each squad, armed with a tablet and a quadcopter-style surveillance drone.

Additionally, the branch plans to augment its platoons and rifle companies with better intelligence cell capabilities, drawing on rank-and-file infantry partnered with dedicated intelligence personnel in an innovation developed during the War on Terror to help ground troops fight amidst the new ideological and informational scope of 21st-century conflict.

As the Forever War continues to evolve into increasingly disparate regions and missions against a new generation of stateless opponents exploiting technological know-how of their own—ISIS’s use of cell phones, off-the-shelf drones and Webb 2.0-savvy propaganda come to mind—and the looming specter of conventional war with well-armed conventional powers such as China and Russia with advanced technological capabilities, the lines between the “boots on the ground,” intelligence agencies and the government’s dedicated cyber-warfare organizations will continue to blur and overlap—and not only within the armed forces, but also with new private sector partners.

Dark lord Saruman uses his Palantir to gather intelligence on a band of irregular, ideologically motivated insurgents plotting a deadly attack on Mordor.

The military has already taken to using private industry big-data expertise in counterinsurgency tools, such as Silicon Valley startup Palantir’s suite of systems for intelligence analysis (named, in an ominous nod to Tolkien lore, after the seeing-stones which allow powerful wizards to see “images of things far off and days remote.”)

In a radical development less than five years old, the military is also beginning to shift the entire nature of its acquisition and deployment process, aiming to incorporate some of the nimble, solutions-oriented, and cutting-edge qualities of Silicon Valley tech culture—as well as its brightest and unorthodox minds—to develop ambitious technologies for military use.

Designed to counter the newly tech-aware insurgencies of the world as well as the threats of advanced IT and military superpowers and keep up with the ever-increasing rate of technological innovation and proliferation, a host of DoD programs have sprouted up in American tech hubs, mirroring aspects of the startup world to hone the U.S. military’s technological edge and break free from the purview of the DoD’s traditionally slow-moving, bureaucratic, and obscenely over-budgeted acquisitions and development process.

In a recent piece by Wired describing one such “Dream Team of Tech-Savvy Soldiers,” the magazine delves into a new program established with the U.S. Army Cyber Command and the Defense Digital Service (DDS), a “sort of tech startup inside the Department of Defense” named “Jyn Erso” after a Star Wars character who steals the plans for the Death Star from the Galactic Empire.

Described at turns by Wired as reminiscent of “the storied garages where Apple and Hewlett-Packard began” or “a scene out of Ocean’s Eleven,” Jyn Erso is a small team of tech-savvy soldiers and Silicon Valley experts dedicated to developing small, cheap, and rapidly deployable cyber solutions for the military while bucking the DoD’s rigid, slow-moving culture and often restrictive practices.

One of Jyn Erso’s breakthroughs in the article included the creation of a portable drone jamming device for use to combat ISIS’ growing use of home-brewed armed drones, which have proven a problem given that the terrorist organization uses off-the-shelf drones by manufacturers such as DJI, meaning that the military has to combat what one DDS Major calls the ever-evolving “Christmas cycle” of consumer tech advancement.

ISIS is employing off-the-shelf consumer drones in surveillance roles or even—as in this picture of a captured drone—as makeshift bombers equipped to drop grenades on enemies’ heads. Via Rudaw.net

The Pentagon has started courting Silicon Valley and leveraging private sector advances in larger projects as well that represent a new and likely lasting shift from the bloat and glacial pace of traditional military acquisitions towards a new marriage of DoD dollars and tech industry know-how, especially on the cutting edge of developments such as robotics, AI and other advanced technologies where the private sector often far outpaces the conventional military.

The most [in]famous of these programs is Project Maven, designed to use the tech industry’s algorithmic expertise in acquiring AI systems for frontline use, notably in the case of computer vision AI developed by Google for object recognition. The military tested Google APIs in frontline service against ISIS for drone surveillance analysis as early as late 2017, until the development gained wide public knowledge.

Media coverage of Google’s Project Maven involvement prompted public outcry and protests among tech industry employees who felt hoodwinked or betrayed by their parent company regarding defense projects, concerned by the ethical dilemmas of defense work or about the technology’s potential first step towards weaponized AI or even autonomous weapons.

The role of the private tech industry in cooperation—or complicity—with the Pentagon in the ongoing War on Terror raises serious ethical, philosophical, technological, and political concerns for many within the Silicon Valley scene, hinting towards larger issues of the growing civil-military divide in post-Cold War America. Despite controversial foreign policy decisions or some tech employees’ reluctance to support them, however, Project Maven and other programs are likely represent a beachhead for more and more ambitious partnerships between Silicon Valley and the DoD.

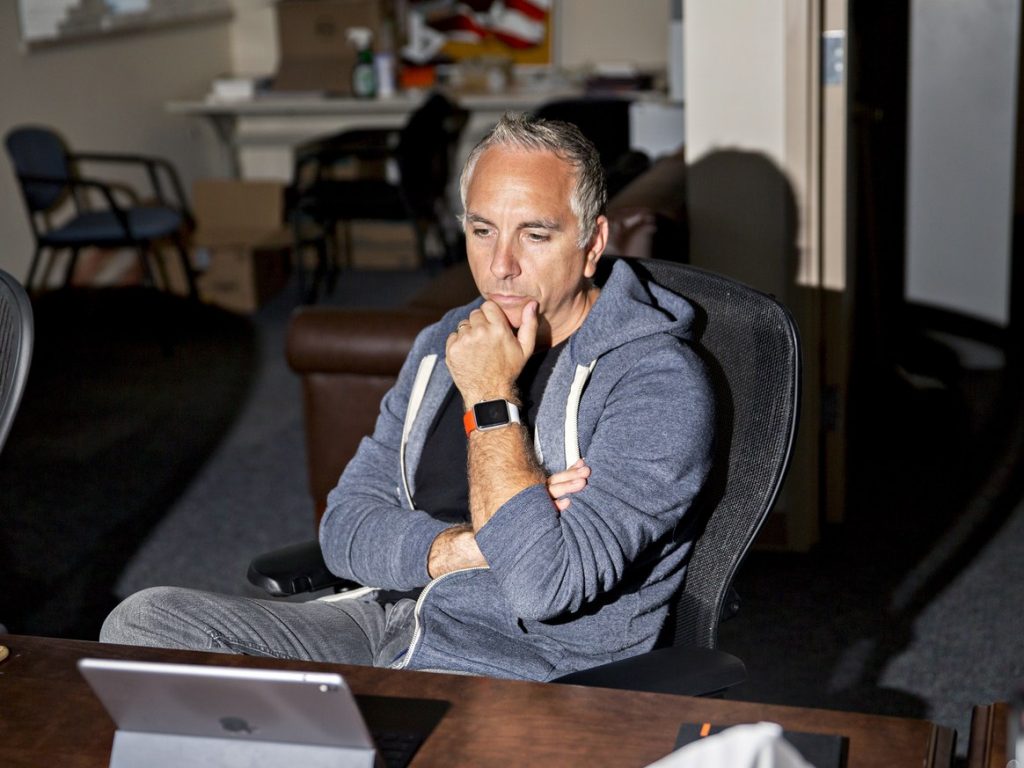

Chris Lynch, director of the DDS. More culturally akin to the startup scene than the rigid world of military brass, DDS and other tech & cyber initiatives are changing the way the military contracts its tools and the tactics it uses to employ them. Via Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg/Getty Images.

While Google quietly agreed to not renew its Project Maven contract and has revised its policy stance to preclude developing potential lethal technologies, the company still aims to provide cutting-edge technology to the DoD, including AI and cloud networking tools for Special Operations forces. According to industry news site DefenseOne, Google pitched cloud networking tools, hardened combat-zone ready devices, and computer vision APIs for intelligence gathering and Sensitive Site Exploitation (a process roughly akin to crime scene investigation) at The Special Operations Forces Industry Conference this May in Tampa, Florida.

In another recent project similar to Maven, the DoD established the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx), “a fast-moving government entity that provides non-dilutive capital to companies to solve national defense problems” including avant-garde tech “from autonomy and AI to human systems, IT, and space” according to the unit’s homepage.

More akin to a Silicon Valley incubator or VC firm than the bureaucracies that traditionally solicited and oversaw years-long acquisition for technologies, DIUx aims to cooperate with the private sector to conscript existing high-tech solutions for military use within mere months or even weeks. DIUx’s portfolio, in addition to some established defense contractors, includes an impressive and growing list of private tech and industrial companies working on everything from robotic drones and boats to AI that may be able to predict vehicle breakdowns.

In an unstable world order marked in the 21st century by the advent of non-state powers such as ISIS as well as the rise of global powers Russia and—especially—China with advanced technologies and global ambitions, warfare as well as every other sphere of life is already being affected by what commentators have coined the rapidly approaching “4th Industrial Revolution”.

Marked by breakthroughs and new uses of technology such as AI, robots, 3-D printing, IoT, and autonomous systems as well as new forms of communication such as smartphones, social networking, and encrypted private messaging, the 21st century will force the U.S. Military to adopt Silicon-Valley style technologies as well as the cutthroat private industry’s governing principle: adapt or perish.

Great delivery. Outstanding arguments. Keep up the amazing work.