UK House of Lords Member Calls for AI Ethical Charter

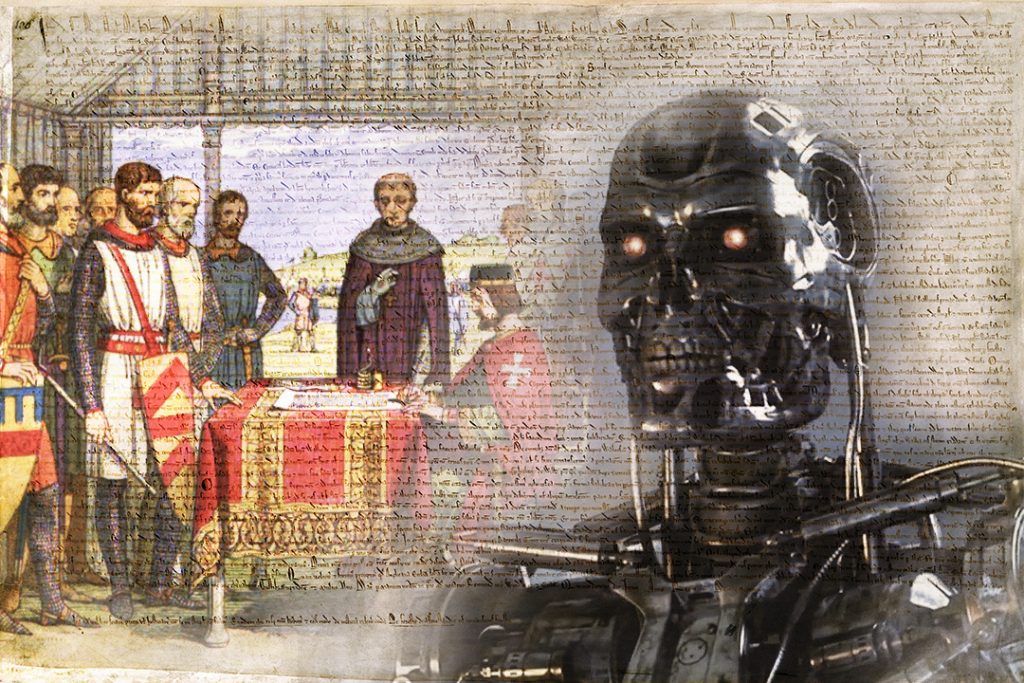

In an editorial published in The Washington Post on May 2, House of Lords member Anthony Giddens calls for “a Magna Carta for the digital age” to reduce AI risks and guarantee the protection of individual rights while also fostering innovation in technology.

Lord Giddens is one of 13 members of the House of Lords Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence in the U.K., which released a report last month entitled AI in the U.K.: Ready, Willing and Able? (pdf here). In the process of researching AI, Giddens and the other committee members interviewed “some 60 experts from different backgrounds in industry, academia and the think-tank world” about the future of AI, “[aiming] to distinguish, as much as possible, the hype and more remote, apocalyptic visions of digital transformations from real dangers.”

Member of the Lords and former sociologist Lord Anthony Giddens. (Image Source)

The Magna Carta—or “Great Charter”—was signed by King John of England in 1215 and is one of the most influential documents in Western thought, first and outlining individuals’ basic rights and the foundational social contracts between ruler and subject that underlay modern governments. Giddens calls for the adoption of an ethical and political code to govern AI development as a modern-day equivalent of the famous medieval document, asserting that “the new kings are big tech companies, and just like centuries ago, we need a charter to govern them.”

Recounting the history of AI development from its first wave in the mid-2oth century to its resurgence in the dotcom-era tech boom, Giddens believes that society is on the verge of an Internet-powered third age in AI. Noting that tech giants’ big data and AI platforms already influence “everything from the intimacies of everyday life to geopolitical struggles,” Giddens warns that unchecked development in AI may imperil the very liberties that the Magna Carta first established:

“For a while, the positive breakthroughs of digital technologies—greater connectivity among like-minded peers or distant scholars, big data analysis of the genetic code, the convenience of online shopping — took center stage. But the negative aspects have proven to be profound, even though they took time to surface. They include threats to the very tissue of democracy itself—online movements have come to challenge or even displace mainstream political parties. These are emerging at the same time as what look like dramatic advances in machine learning.”

To counter the looming specter of hastily-developed, monopolized AI systems, Giddens recommends that the U.K. and other nations first need to embrace “radical intervention to help break down digital corporations’ data monopoly and allow individuals greater personal control over their data and how it is deployed.” Giddens also outlines what a 21st century Magna Carta might look like, suggesting that world leaders should assemble to address the urgent need of creating an internationally-recognized AI code of conduct, a “common framework for the ethical development of AI at the global level.”

As a tentative charter for AI ethics, Giddens proposes that AI:

• Be developed for the common good.

• Operate on principles of intelligibility and fairness: users must be able to easily understand the terms under which their personal data will be used.

• Respect rights to privacy.

• Be grounded in far-reaching changes to education. Teaching needs reform to utilize digital resources, and students must learn not only digital skills but also how to develop a critical perspective online.

• Never be given the autonomous power to hurt, destroy or deceive human beings.

For more information including specific concerns about the UK’s handling of NHS healthcare data, read the rest of Lord Giddens’ article.

Leave A Comment