Don’t be Evil: No Easy Answers for Google’s Moral Dilemmas

“For many years I’ve been ashamed, mortally ashamed, of having been, even with the best intentions, even at many removes, a murderer in my turn. As time went on, I merely learned that even those who were better than the rest could not keep themselves nowadays from killing or letting others kill, because such is the logic by which they live, and that we can’t stir a finger in this world without the risk of bringing death to somebody. Yes, I’ve been ashamed ever since I have realized that we all have the plague, and I have lost my peace.”

—Albert Camus, The Plague

If you are looking for easy answers in the world of AI ethics, none readily exist—especially in the murky boundaries of defense contracting. But these are issues we cannot afford to reduce to simple terms or, worse, outright dismiss, given the genuinely life-and-death consequences of AI systems that Project Maven highlights.

Google’s former code of conduct. (Image Source).

Last month details about a Google program to assist the Department of Defense with drone surveillance AI received widespread media coverage and analysis, raising questions about the role of the tech industry in assisting Pentagon war efforts. Outraged Google employees wrote an open letter with thousands of signatures to company leadership decrying what they viewed as actions in violation of Google’s once famous ethical charter “Don’t be Evil.”

While many members of the tech community might have no qualms or, conversely, even feel proud to know they are in some small part supporting American war efforts, others might find themselves troubled over the creation of lethal technologies assisting in war.

I cannot fault the Google employees for their convictions in demanding that the company cease activities with Project Maven and stop present and future cooperation with the DoD. While a former DoD employee myself with friends and family still in the U.S. Military, I can also understand that—unlike myself—none of those employees signed up so they might serve war in some capacity; indeed, many may have sought out Google precisely for the company’s ostensible commitment to an ethic of doing good. None of the Google employees concerned over Project Maven likely imagined his or her creations might make them, to quote Camus “a murderer […] at many removes,” though Project Maven is the impetus for workers in the AI space to reexamine—as they ought to—the potential impacts of their technologies.

Regardless of how the Project Maven situation ends, Google ought to have been more forthcoming about active Defense projects to avoid putting its employees in the indirect service of a war none of them chose to serve in.

Google and other employers in the space must hold themselves accountable and forthright in the coming AI age. Regardless of one’s views on Project Maven or similar technologies, it’s vital that these programs be discussed and ample discussion and even dissent be allowed within tech companies. We must make sure AI research moves forward with the least amount of direct harm and unintentional results possible, as the potential consequences are deadly.

This debate takes place amidst of the growing scope of The Global War on Terror (GWOT)—America’s longest, and a conflict even military leadership calls without a hint of irony “The Forever War.” The coming AI Age means such distinctions will become more inextricable as lines between peaceable and defensive or offensive uses of AI blur. Even with the best intentions, more than ever it’s a time of high stakes and potentially deadly unintended consequences for the tech sector.

Navigating the complexity of Project Maven challenges us to think in new ways about the ethics of AI use—offensive and civil alike. We must explore how even well-intentioned or limited AI use can risk opening a proverbial Pandora’s Box in the future if we neglect sober consideration today for downstream consequences and fail to implement judicious oversight of AI development and employment. AI developers, technocrats and lawmakers cannot afford to defer such responsibility or dismiss it altogether.

Rapid Rollout for an Urgent Need

A soldier in Iraq launches an unarmed RQ-11 Raven drone used for ground surveillance. (Image Source)

Project Maven—or the Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team in defense lingo—was founded by the DoD scarcely a year ago in April 2017 in response to the U.S. military’s dearth of cutting-edge machine learning tech compared to the private sector. Growing threats of Russian and Chinese military AI development spurred the department into action.

According to an illuminating article published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in November before the project gained widespread public exposure, Project Maven represents an ambitious proof of concept to catalyze the rapid development of military machine learning technology by partnering with academic and private sector experts to streamline the laborious acquisition process down to a blistering six months.

Military contracts, while vastly lucrative, are by their nature long and arduous processes rife with bloat, bureaucratic roadblocks and the myriad ever-changing requirements of the military. Consequently, private sector companies are reluctant to undergo the long process. The military, in turn, often ends up with technologies that are cumbersome and dated by the time they are ready. This is most obvious in the technology space, where private sector companies make breakneck progress in months, while government contracts often linger for years in development, all but guaranteeing their rapid obsolescence.

Project Maven’s first test was to acquire image recognition AI for drone video analysis, a task likely chosen—according to the Bulletin article cited above—because of its relative ease of development and low risk. Academic and private sector advisors suggested Maven begin with “a narrowly defined, data-intensive problem where human lives weren’t at stake and occasional failures wouldn’t be disastrous.” Rather than assume difficult, time-intensive, and politically unpopular projects such as AI for direct targeting or weaponized uses, Project Maven’s partnership with Google meant it had only to retrain existing open-source image recognition AI for use in military environments, where the technology would be used, according to Google, only for “non-offensive uses only.”

According to the original Gizmodo article which broke the story in the mainstream press citing both Google and DoD sources, Project Maven uses open-source TensorFlow APIs trained on relevant imagery to enable “the automated detection and identification of objects in as many as 38 categories captured by a drone’s full-motion camera” and “track individuals as they come and go from different locations.” According to statements by Google, Project Maven only “flags images for human review,” and won’t be used in direct operations to fly drones or launch weapons. Ultimately, Google says, the technology will both “save lives and save people from having to do highly tedious work.”

Project Maven aims to ameliorate the Sisyphean challenge of reviewing the military’s vast stores of drone footage. Increasingly used in combat theaters in recent decades, both armed and unarmed drones contain arrays of visual, infrared, and radio sensors to collect ISR—Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance—for combat forces. The crucial task of watching and analyzing drone footage falls on members of the military and intelligence community, who manually watch drone footage to identify threats (and, conversely, noncombatants), track individuals’ movements, and glean other intelligence.

Inside the “cockpit” of a Predator drone. American drone personnel and intelligence analysts face the seemingly impossible burden of making sense of terabytes of footage per mission, a massive and growing backlog of data of which only a small percentage is even viewed. (Image Source)

Overburdened in the ever-expanding GWOT and facing challenges such as combat stress, overwork, cultural barriers of foreign areas of operation and the inherently boring and tedious nature of their work, analysts of all ranks and agencies have the impossible challenge of drawing potentially life-and-death information from a cache of video and imagery so vast it would take many human lifetimes to watch, let alone analyze. Estimates conclude that only a small percentage of drone footage is ever analyzed, meaning that vital details are likely lost. Human analysts waste valuable time and resources on insignificant data.

For example: a drone flies an ISR mission over Afghanistan (or just as likely, in Somalia, Yemen, Syria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Niger, et. al.) as countless many are doing right now. The mission might last for hours, during which a drone will record hours-long reels of seemingly inconsequential footage of pastoral countryside, small villages or a teeming bazaar.

Our hypothetical drone’s pilots and observers watch the craft’s video feed; nothing obvious happens. Or does it? Two weeks later, friendly forces hit an IED in the same region or discover that a local warlord with a penchant for funding radical militants might have a safe house in the area. Yet more staff, as young as 18 and living under the demanding stressors of a combat deployment, are then assigned view and pore over the hours of earlier footage, seeking proverbial needles in an electronic haystack. It’s the crucial work of these personnel watching drone footage which, directly or indirectly, decides what future actions might be taken in our hypothetical Afghan village—from armed drone strikes to ground assaults to political measures. This example hints not only at the glaring need of Project Maven’s use, but also at some of the uncertain moral terrain of drone use.

Google’s Project Maven support isn’t—as far as we’re aware—employed in lethal situations. Intended to relieve a heavily burdened military by better sorting through and analyzing drone data, it will help improve the effectiveness (read: lethality) of American forces. It also will, indirectly, decide who dies, who doesn’t and why.

The Moral Uncertainty of Technology in Modern War

That Google and the DoD claim the program is not being used directly to kill aboard armed platforms is likely of little reassurance to those with ethical qualms over supporting Project Maven. Project Maven technology is only scant degrees removed from the proverbial pulling of the trigger. While human intelligence personnel and commanders on the ground have the ultimate say in the lethal actions of troops, drones and other deployment of lethal force, these actions will be informed—one could argue, for the better—by the improved analysis of surveillance. Maven technology could be used and is likely already being employed to identify and track targets or otherwise assist in lethal operations. In short, people will die—or not—as a direct result of insights gleaned using Project Maven.

For instance, Maven technology might be able to sort through the hours of drone footage in the aforementioned scenario, rapidly identifying patterns and individuals within the footage, uncovering intelligence that could take humans days or weeks of strained viewing to uncover, if ever. Such technology could be used with superhuman accuracy to target and track the people and places associated with one of the military’s High Value Targets—such as an ISIS or Taliban shadow governor, a prolific bomb-maker, propagandist or corrupt warlord.

In another example, a drone operator providing overwatch to ground forces using Project Maven technology could instantly identify a man—or for that matter, a child, if we’re on the subject of queasy ethical quandaries—ferrying bomb-making materials or a machine gun near the path of troops. These are threats that a human being watching drone imagery might miss or even be incapable of identifying. While yet unspecified, the specific TensorFlow APIs used in Project Maven are likely identical or similar to Google’s “Inception” Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), which can spot objects in still images with accuracy far beyond the capabilities of humans—if it works perfectly, and if it has been “trained” (in neural network lingo) to identify the objects presented to it.

Given the potential for Project Maven technology to grant superhuman accuracy to drone analysts, such technology might paradoxically make America’s Forever Wars less hellish as a direct result of improving the identification and analysis of objects in drone feeds. ISR is only as accurate as the sensors and cameras used and those of the human analyzing the footage. By using the full extent of the former and improving on the latter, Project Maven AI might help military personnel cut through the “Fog of War” with a peerless digital gaze trained in millions of sample images, capable of pixel-by-pixel analytic capabilities. The technology is also immune to the pitfalls of personal biases, hunger, sleep deprivation or simple inexperience.

Above: Focusing on the controversial usage of armed drones above today’s battlefields, this video highlights many of the technological and tactical problems encountered by the military. (Video Source)

The Global War on Terror has claimed, according to estimates which vary wildly, hundreds of thousands and likely more than a million civilian casualties. Many innocent lives have been lost across the globe in the wars authorized under Congress’ post-9/11 Authorization for Use of Military Force and its authorization for the Iraq War. Civilian deaths are a widely publicized—and criticized—cost of American foreign policy. Armed drones have killed noncombatants at wedding parties, funerals or schools in pursuit of military targets. An independent estimate concluded that nearly 90 percent of those killed in U.S. drone strikes were not the intended target.

While far less destructive than conventional airstrikes, use of armed drones has nonetheless garnered controversy both domestically and abroad, damaging U.S. perception on the ground in communities beneath drone operations. Collateral damage is counterproductive in the crucial ideological and political spheres of the War on Terror and likely creates more enemies, especially among the tribal societies American forces interact with such as the Pashtuns. The ethnic group forms the historical base for the Taliban—for whom close ties and the strictures of honor-bound revenge mean that even neutral or pro-Western populations might be irreparably radicalized by a single wayward drone missile or wrongly directed ground raid.

Combat mistakes caused by bad intelligence and clouded judgment also affect drone pilots, soldiers on the ground and other military personnel. They are facing generational a crisis of PTSD from combat situations and “Moral Injury,” the deep emotional and spiritual scars even highly trained military personnel risk in the difficult situations they face in an increasingly ambiguous war, such as the accidental killing of civilians.

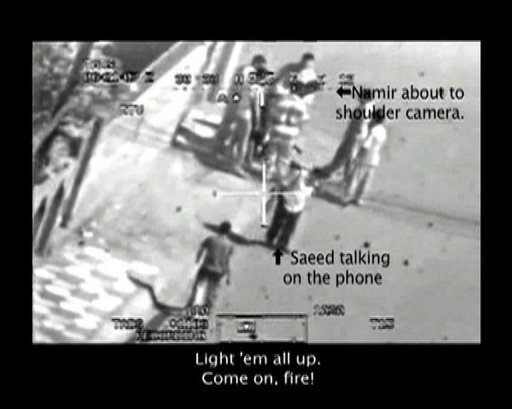

Above: Screengrab from “Collateral Murder”, a video released via Wikileaks showing Reuters journalists killed in a helicopter strike in Iraq. The men, carrying camera equipment, were purportedly mistaken for armed militants. (Image Source)

While Project Maven AI is not, as far as we know, employed on the armed drones executing such strikes, drone strikes and other military actions are a direct result of intelligence gathered in ISR operations by systems that might use or soon be using Project Maven technology. Such technology might reduce the tragic mistakes.

A human pilot or analyst today might watch amorphous infrared heat signatures near a building targeted for a strike and see a squad of militants; an AI might accurately identify them as women and children at a daycare, or even a pack of mischievous monkeys raiding a vacant farmhouse. A human may see a military-aged male wielding a rocket launcher, while an AI might conclude instead that footage is of a boy carrying a shovel or a journalist carrying a camera. A human might miss an almost imperceptible anomaly that an AI might reveal to be an IED lying in wait.

Project Maven will result in deaths, and any insistence otherwise represents a gross naivete of how and why military operations are conducted today. However, should Project Maven be embraced as a potential way to lessen the cruelty of an already vastly destructive worldwide campaign that shows no signs of abating after 17 years? Consider that it may also save the lives and consciences of American troops by providing them with more effective intelligence and targeting information.

In the absurd calculus of warfare, if Project Maven AI helps to indirectly save a squad of 13 young American soldiers or Marines by diverting them from an ambush that a human analyst would not have noticed, would the program be worth it? What if the same intelligence meant that these troops killed a team of enemy militants in a hidden position the Project Maven AI discovered? Would it matter if the Project Maven AI helped prevent a raid or drone strike on a school of 50 children that might have otherwise been mistaken for an enemy stronghold? Such uncomfortable questions are reminiscent of ethics’ classical “Trolley Problems,” with no easy conclusion.

A neutral machine intelligence capable of instant recognition and classification of objects could better able to analyze footage and make snap judgments than a 20-year-old Lance Corporal or Senior Airman or Specialist running on adrenaline and caffeine with little or no sleep. Humans relying only on observational faculties worn thin by combat stress and boredom may not have the ability to discern the need to act.

I can easily put myself into the shoes of those most affected down range from glitzy headquarters of Silicon Valley corporations—I was once the 20-year-old grunt Lance Corporal on watch for enemy activity on distant outposts in Helmand Province. My platoon was protected by a variety of high tech ISR systems, systems that also provided invaluable intelligence for our day-to-day patrols and operations, and technology such as Project Maven would have been a welcome boon to our ISR and force protection capabilities and may have saved lives.

But even if graced with a narrow superhuman ability to identify objects or people and track them, what if Project Maven AI is used by accident, or on purpose, to kill the wrong people?

Potential Vulnerabilities, Unintended Consequences

Even if better than almost any human put to the task, Project Maven AI might suffer from as-of-yet unknowable flaws and fatal errors. In one example of the fallibility of superhuman image identification AI, one mistook a turtle for a gun.

In addition to the questions raised by malfunctioning AI or AI used perfectly but potentially towards morally troubling ends, military AI systems could also be used in different scenarios than originally intended. If a Google engineer is willing to support, say, Project Maven on the grounds it is not directly used to launch weapons, or if another even views support of Project Maven as his or her patriotic duty regardless of the outcomes, the technology might easily be envisioned to be used for different, more nefarious purposes.

Image recognition AI such as that employed by Project Maven or used by self-driving cars can be fooled by simple abnormalities in an environment, such as simple graffiti which defeats AI trained to identify traffic signs. (Image Source)

In another troubling example of AI error, image recognition AI can be fooled with alteration as minor as a single pixel, a glaring vulnerability if drone data were to be hacked or “poisoned.” Potential adversaries could even learn such vulnerabilities of military AI and in turn adopting novel new Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) to fool AI.

Finally, it’s vital that Project Maven be made as impartial as possible and imbued with the same kinds of crucial cultural awareness training mandated for combat zone personnel in as the GWOT progressed as part of the U.S. Military’s Counterinsurgency (COIN) strategy. Project Maven technology may be eventually trained to recognize all manner of military hardware in any environmental conditions, but should be trained on images relevant to the regional cultural environment where it is employed to avoid tragic consequences of, say, mistaking a Somali or Afghan farmer’s scythe for a radio antennae or rifle barrel. The corruption of algorithms by implicit, subtly biased data is already an endemic problem in AI and big data. In a military AI system, it could have deadly costs.

Even in the best-case scenarios outlined earlier, however, Project Maven cannot entirely eliminate the “Fog of War.” Even if it works perfectly, it only informs military intelligence personnel and commanders and does not—not yet at least—assume the tactical or moral responsibility for actions taken as a result. Humans are the sole and final arbiters in the loop of lethal consequence. We have not yet abdicated the solemn responsibility of warfare to machines. AI such as Project Maven can only better inform the troops on the ground, who in turn are only acting on the moral and legal authority of the politicians and strategic minds who send them to war.

If an AI might tell the difference between a man carrying a rifle and a shovel far better than a human, does it salve the conscience of a conflicted Google engineer if, for instance, current Rules of Engagement (ROE) still permit the killing of someone carrying a shovel if they are suspected of placing an IED?

While the Google employee protest letter acknowledges the technology’s ostensibly nonlethal aims, employees expressed concern that the technology might leave control of Google or Project Maven. Once the DoD or Google completes or otherwise ends the initial Project Maven contract, the DoD will still retain possession of the newly trained AI and could easily, officially or otherwise, use it for more ambitious projects. The same AI used on surveillance drones might be employed on other ISR systems such as spy satellites or ground-based security cameras. More troubling, having trained Project Maven AI on a variety of military-specific imagery, it would be trivially easily to port the technology for use on armed drones or the Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS) which will almost assuredly gain use in the coming decades.

Much in the way that NSA malware has been stolen and employed in a series of costly heists and hacks worldwide, government AI might also be leaked or hijacked by malicious actors. Other superpowers are already developing their own drones to rival America’s remote systems, and even terrorist organizations such as ISIS have also employed their own homemade drones. Other nations and non-state actors will not likely share Americans’ historic caution or moral compunction in development and employment of AI-supercharged surveillance or weapons systems.

Similarly, even without worst-case scenarios of being developed into “killer robots” or falling into enemy hands, Project Maven could fulfill discomforting aims. The same drones and other ISR systems used abroad in the Global War on Terror are finding increasing use above American soil by domestic law enforcement agencies, mirroring a troubling post-9/11 trend of what commentators see as an increasing use of Forever War equipment and TTPs employed against American citizens.

Don’t be Evil

Google CEO Sundar Pichai. “Good, Bad … I’m the guy with the most advanced open-source AI libraries in the world.” (Pichai Image Source, Army of Darkness Image Source)

A significant number Google employees or customers, troubled by the ethical quandaries outlined so far, might decide that they simply do not want any part in technology that might be used—even indirectly—to kill people in war. Others might see this stark reality as a conflicting gray zone. Even if Project Maven were to work perfectly and increase the effectiveness of American troops fighting ISIS while minimizing civilian casualties, the very nature of modern warfare means that for all its benefits, Project Maven might yet implicate Google in as-of-yet unforeseeable acts of war. Google ought to be as forthright as possible to its internal teams and the public alike about the present and future uses of its defense technologies.

Additionally, if Google continues its Project Maven work or further assists DoD projects—after historically maintaining a distance from such contracts in comparison to competitors Microsoft and Amazon who have embraced large-scale government and defense work—the Google employee letter suggests that the company might be seen to betray its founding principle of “don’t be evil.” If it does, Google will join the ranks of companies such as Raytheon, Lockheed Martin and Palantir technologies, which are well-known in the public eye for involvement in large-scale defense projects. The business of making war technology is a lucrative but also morally and politically risky one. America’s most decorated historical military leaders—Dwight Eisenhower and Smedley Butler, for instance—have decried the troubling marriage of unchecked private profit and the proliferation of war.

What if Google employees were to refuse to participate in Google’s defense projects or customers were to protest, boycott, or otherwise pressure the company firmly enough that Google ceased DoD involvement? If we can imagine how a conflicted Rosie the Riveter might have a change of heart and decide that she is uncomfortable building warplanes, might a talented Rosie the AI Coder who’s just discovered that her AI is used in combat zone ISR platforms choose to absolve herself of moral guilt by refusing to develop AI for combat zone ISR systems? Especially if the AI might be developed into more explicitly lethal purposes.

Or would Rosie’s least-evil course be to develop a technology that might save the lives of American troops and minimize harm to innocent noncombatants alike, while holding Google and our lawmakers transparent and accountable? If we assume that any technology employed to assist in war and by some many removes kill is indeed evil, might Project Maven make war less evil? If Google doesn’t provide AI for Project Maven or other DoD Projects, but some other company does, it might be a company with far fewer compunctions.

I am not arguing that conflicted customers or employees of Google salute the flag, quell their consciences, and double down in support of Project Maven, and neither am I suggesting that defense technologies ought not exist. I once relied upon their products—from automatic rifles to toilet paper to Palantir when I was in a combat zone. The hard questions don’t have clear answers, but they demand our careful consideration.

The dawn of the Age of AI is upon us, and ours will soon be a world governed increasingly by the dictates of big data algorithms and ever-more advanced AI systems. AI developers must guard themselves against the “nerd-sighted” foibles of assuming that, even with the best intentions, their actions are not committed in a vacuum devoid of ethical, legal or political consequence.

AI engineers, such as the brilliant minds at Google responsible for creating the open-source computer vision technology likely behind Project Maven, did not exercise their own vision to imagine how such technology could be weaponized with relatively trivial ease. Nor did other AI engineers likely intend that their neural networks might be employed to out homosexuals or one day lead to an Orwellian future of algorithmic-reinforced physiognomy which in turn may lead to social classification or eugenics programs.

But AI can do good; image recognition AI can be used to rapidly diagnose skin cancer, help farmers in the developing world to identify sick plants and even aid scientists chart the histories of galaxies, among a host of other beneficial world-changing applications yet to be conceived.

The Project Maven AI’s code is not in and of itself “good” or “evil,” as amoral and uncaring as the liquid steel which can be forged equally alike into a plowshare to cultivate food or a rifle to kill for purposes justified or barbarous. AI can assist the aims and impulses of the human race in scarcely imaginable magnitudes, but will not of its own accord—at least not for many decades hence, if ever—develop a conscience of its own, and moral responsibility for AI present and future lays squarely upon our shoulders. In Project Maven, we see a parable of the complex realm of AI ethics and a sign of even more confounding quandaries to come.

I certainly don’t want to see the carnage of war meted further upon the people of any nation, but I also realize that such a prospect is, unfortunately, impossible. Having relied on ISR and its subsequent analysis in a combat zone as a young Marine and having as well seen the consequences of the innocent caught in war’s crossfire, if I were in that situation today I would unhesitatingly vouch for any technological advantage possible—including Project Maven—at whatever material cost. Project Maven’s potential—if applied correctly—will minimize loss of innocent life and protect American troops. I count among my friends and family those who also served in the military and still do, men and women whose lives may be directly affected by the outcome of defense AI projects such as Project Maven.

I am certain that these questions are ones worth asking of the technological, corporate and political powers overseeing the AI systems that will soon control the course of our lives, if not human history. If AI programs are prematurely rushed or used wantonly, the potential downside is incalculably dire.

Regardless of the future of Project Maven in particular or of future DoD cooperation with Google or other private sector talent in AI, the government and any private or academic contractors involved must be as open and transparent as possible. They should be willing to operate within the confines of rigorous public oversight and legislative authority⎯ideally under the guidance of a new AI culture of healthy caution, critique and collaboration. Ethical codes for AI research should be established and codified into practice across the globe, or at least in the United States.

I commend the employees of Google who are protesting their CEO—if not necessarily out of agreement with all of their tenets, but rather for their moral courage and their commitment to question the ethical import and long-term consequences of the immense technological responsibility they wield. For this, they are to be saluted as the moral leaders of their field when far too many of their peers and superiors are simply dismissing the grave risks of AI gone awry.

Leave A Comment