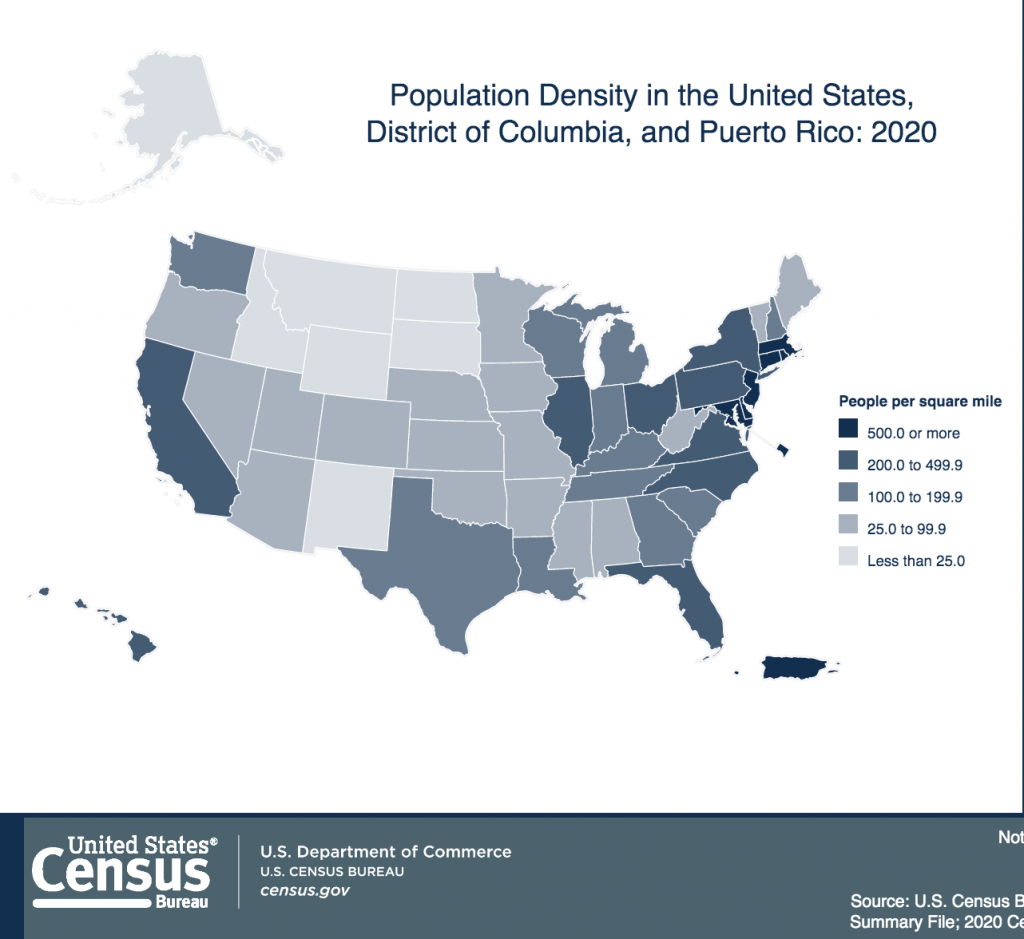

Due to undercounting the population, the Census Bureau is turning to AI and satellites for more accurate numbers.

Extreme Effects of Undercounting Citizens Could Be Corrected by the Use of AI, Satellite Imagery

One of the U.S. government’s failures during the pandemic is the undercounting of citizens in the U.S. census. Since 1790, the agency has tried to count the population with varying degrees of success. But the last census in 2020 run by the Trump administration appears to have been way off the mark on several matters.

Since our legislative districts are drawn from the census count, it is vital to get it right for fair representation.

A disturbing article published in wired.com shines some light on the recently undercounting of various ethnic populations and the possibility that using AI might help solve some of the problems.

Most U.S. census forms were filed online instead of on paper in 2020. Information from federal agencies like the IRS and location data from private brokers helped to update addresses or add new ones. Automation helped with field staff recruitment, hiring, training, and payroll. The Census Bureau also used software to classify new construction projects seen in satellite imagery for the first time, an approach that added 5 million new addresses to a list of households in the country.

In contrast, virtually every address recorded in the 2010 census was verified by a person who physically went to that location. By 2020, that had shrunk to just 35 percent. As the story explains:

“Despite applications of new technology, the census still got plenty wrong. Estimates suggest Native Americans were undercounted by 5.6 percent, while the Hispanic or Latino census category had the second-highest undercount, at an estimated 4.9 percent. Children ages 0 to 4 were undercounted by an estimated 2.79 percent. The U.S. Census Bureau recently assembled a team to research why it’s so hard to count young children, and a breakdown of housing units undercounted in 2020 is due out this summer.”

How AI Can Assist

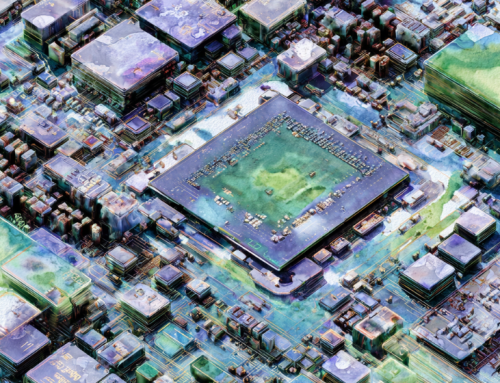

The Census Bureau is now working on a machine learning algorithm that detects new construction, using satellite imagery to track projects from start to finish. Developed with input from Statistics Canada and an automation and analytics consultancy, the initial prototype achieved accuracy rates of about 90 percent. In the year ahead, the U.S. Census Bureau will test its AI in different parts of the country to see how the model performs in various climates and regions.

Designers of the system use building permit data to validate initial results, an approach they suspect will make the model more accurate in places where new construction projects don’t require a building permit. If all goes according to plan, the Census Bureau wants to eventually make construction activity data available as a means of tracking local economic activity down to the zip code.

Those who support using machine learning to analyze satellite imagery believe the two systems can work together to help solve big problems, like protecting the Amazon rainforest, combating poverty, or more accurately estimating the number of people in a given area. But experts building these models say that when they’re used to counting people, they’re still prone to mistakes.

There have been accusations that the last administration didn’t do what it should have in the 2020 counting. Before becoming the director of the U.S. Census Bureau, statistician Robert Santos accused the Trump administration of sabotaging the population count. Upon release of data last month, Santos told reporters he wasn’t surprised by the Hispanic or Latino undercount. Census Bureau focus groups showed similar reservations before the start of the count. Santos said the pandemic—which put people out of work and exacerbated hunger and housing issues—impacted everyone, but especially Latinos.

Among other issues affecting the results of the pandemic, wildfires, and even hurricanes might have contributed to the undercount. But new technologies bring hope that the effects of such catastrophic events can be corrected.

“In research published last month, satellite imagery and machine learning were used to automatically identify housing plots and predict population, age, and sex in five provinces in the western half of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The project brought Grid3 participants like the University of Southampton in the UK together with groups like the DRC’s National Bureau for Statistics. Anonymous surveys of nearly 80,000 people were carried out by the Kinshasa School of Public Health and the University of California, Los Angeles School of Public Health to validate the performance of a deep learning model that achieved about 80 percent accuracy.”

Perhaps the algorithms being unleashed on the census can make progress that can translate to fewer problems for population counters and the legislative districts to be decided upon.

That will have to wait for the next census in 2030. The is a lot more information regarding the use of AI and satellites for taking the census in the link below.

read more at wired.com

Leave A Comment